By Mark Tausig

The New York League of Conservation Voters prioritizes frontline environmental communities to reinvigorate the economy, support a modern workforce, and promote sustainable projects.

There are good reasons to do so. Frontline environmental communities are communities that experience the worst impacts of climate change and environmental injustice. These are communities experiencing high levels of exposure to polluted air, hazardous materials, polluted water, and climate change. Such communities have few resources and low access to safe and healthy housing, food, and healthcare. These communities are often associated with higher rates of poverty, poor health, and racial and ethnic minority populations. The 2019 New York Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (Climate Act), one of the most ambitious climate laws in the nation, prioritizes such Disadvantaged Communities and the creation of good, family-sustaining, union jobs accessible to all New Yorkers. The Act sets the course for New York to create new job opportunities, support healthier communities, and ensure that all New Yorkers will benefit from investments in the State’s growing green economy.

“A fundamental objective of New York’s nation-leading climate and energy agenda is to ensure that New York’s transition to a clean energy economy addresses health, environmental, and energy burdens that have disproportionately impacted underrepresented or underserved communities (including people of color, indigenous populations, low-income individuals, and women) and to remedy the structural causes that underpin these burdens.” —New York State Climate Action Council Scoping Plan.

Addressing climate change cannot be separated from social, economic, and historically driven variations in community exposure to pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, and environmental hazards. That is, frontline environmental communities. The impact of climate change is felt differently based on the environmental advantages and disadvantages of communities.

The New York State Climate Act requires that Disadvantaged Communities receive a minimum of 35%, with a goal of 40%, of the benefits of spending on clean energy and energy efficiency programs, projects, or investments in housing, workforce development, pollution reduction, low-income energy assistance, energy, transportation, and economic development.

By definition, approximately 35% of New York State census tracts are also defined as Disadvantaged Communities (DACs). Thus, the State seeks an equitable distribution of climate-related funding to address prior environmental injustice. The State uses 45 indicators of environmental vulnerability, population characteristics, and health status to identify DACs. DACs are spread throughout the State and vary by conditions that place them in the disadvantaged category.

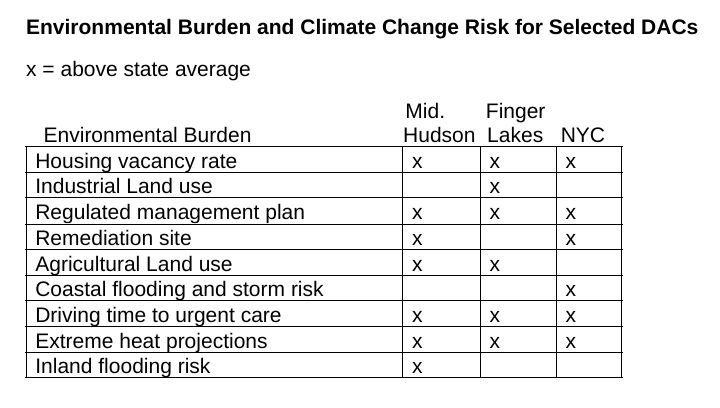

In the table below, we show, for example, some environmental vulnerabilities that characterize randomly selected DACs from several regions of New York State. The differences by DAC mean that redressing climate change and environmental injustice will differ by the characteristics of each DAC. Programs can be selectively targeted to address the environmental, social, and economic factors that place communities in this disadvantaged category.

Despite differences in the environmental burdens found in different DACs, the residents of every Disadvantaged Community experience high levels of health-related concerns. These include high levels of asthma-related emergency department visits, high levels of COPD emergency department visits, high levels of heart attack hospitalizations, high levels of premature death, high levels of low birthweight babies, a high percentage of uninsured residents, high levels of disabilities and high levels of vulnerable adults over 65. These health-related conditions are all linked to exposure to various environmental hazards.

“Climate investments, therefore, are also health investments that will meaningfully reduce pollution in communities and buildings by decreasing harmful emissions and improving air quality. For New Yorkers, this means cleaner air, avoiding tens of thousands of premature deaths, thousands of non-fatal heart attacks, thousands of other hospitalizations, thousands of asthma-related emergency room visits, and hundreds of thousands of lost workdays”.

—New York State Climate Action Council Scoping Plan

Addressing environmental injustice also means addressing long-standing inequality in community resources such as economic well-being, employment opportunities, and quality housing and healthcare. Invigorating the local economy and developing a modern workforce within communities improves the resources within DAC communities by addressing inequalities that characterize them. In this sense, environmental injustice is recognized as a consequence of poverty, racial/ethnic segregation and discrimination and its environmental impacts. Creating clean, green schools, solar energy facilities, heat action plans, using electric school buses, and emphasizing building decarbonization in DAC communities contribute to environmental and social equality.

Achieving environmental justice will require all New Yorkers to have the same degree of protection from environmental and health hazards and equal access to decision-making about creating a healthy environment to live, learn, and work.

Environmental justice is the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people, regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, in developing, implementing, and enforcing environmental laws, regulations, policies, and activities and in distributing environmental benefits. Environmentally Disadvantaged Communities identify environmental injustice and specify remediation targets.

Climate investments are also health investments. Improving the environment can be measured in reduced rates of health concerns and their unequal social and economic distribution. Improving the climate with attention to existing environmental inequalities also implies reducing broader social, economic, health, and racial disparities.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The New York League of Conservation Voters’ policy objectives address protecting our environment, tackling the climate crisis, and safeguarding public health. NYLCV develops policy agendas that lay out specific legislative and budgetary remedies tailored to different levels of government and regions of the state. They serve as practical blueprints to help guide elected officials, policymakers, political candidates, voters, and the general public toward a more sustainable future. Although policy agendas are developed and promoted to improve people’s well-being and health, the ins and outs of the policy advocacy process can obscure this ultimate objective.

In this series, Policy Means People, the policy agenda of the New York League of Conservation Voters will be described in terms of the human outcomes that will follow from the successful implementation of policy recommendations. We aim to trace the links between policy objectives and the lived experiences of people affected by that policy. Policies have in common that the proposed action will result in a beneficial outcome, but the mechanism(s) whereby this can occur are often left unspecified.

Mark Tausig, Ph.D., is a volunteer writer for the New York League of Conservation Voters. He is a retired Professor of Sociology, where he studied health disparities, social networks, work and mental health, international health, and population aging in low—and middle-income countries. His latest book, Population Aging in Societal Context: Evidence from Nepal, will be published by Routledge later this year (2025).